Časová pásma

Přečtěte si následující článek o vzniku časových pásem a poté odpovězte na otázky:

- Co je to pravý sluneční čas?

- Co znamená zkratka GMT?

- K čemu potřebovali námořníci přesný greenwichský čas?

- Co vedlo k zavedení jednotného času pro celé státy?

- Jak vypadají časová pásma dnes?

- Česká republika se nachází v časovém pásmu GMT+1. Co to znamená?

- Jaký je časový rozdíl v pravém slunečním čase odpovídající 1 stupni zeměpisné délky?

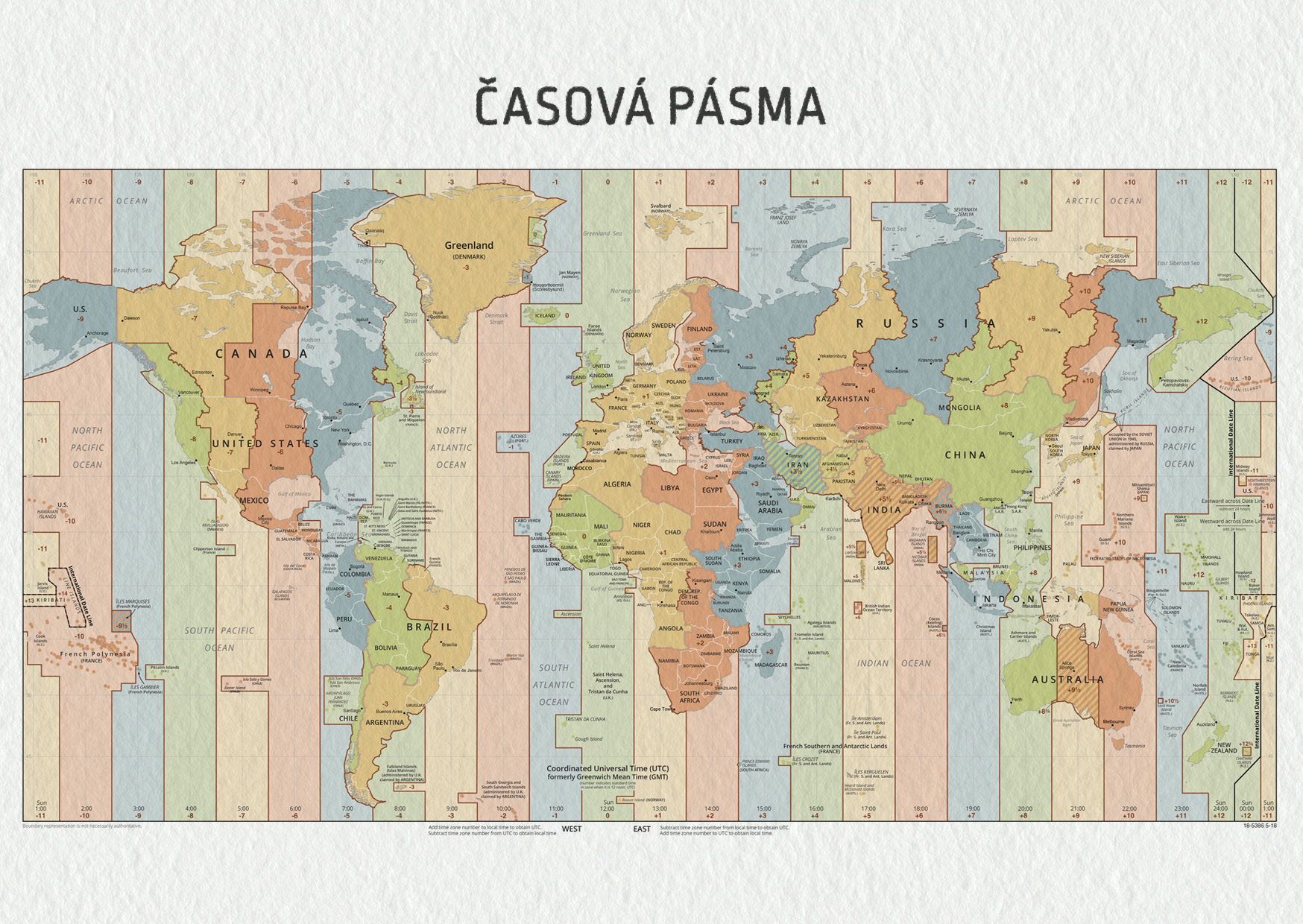

- S využitím mapy vypočítejte, o kolik dříve vychází Slunce v nejvýchodnějším bodě našeho časového pásma oproti jeho nejzápadnějšímu bodu.

Before precise clocks were invented, it was common practice to mark the time of day with true solar time – for example, the time on a sundial – which was typically different for every location and dependent on longitude. Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) was established in 1675, when the Royal Observatory was built, as an aid to mariners to determine longitude at sea, providing a standard reference time while each city in England kept a different local time. Local solar time became increasingly inconvenient as rail transport and telecommunications improved, because clocks differed between places by amounts corresponding to the differences in their geographical longitudes, which varied by four minutes of time for every degree of longitude.

The first adoption of a standard time was on December 1, 1847, in Great Britain by railway companies using GMT kept by portable chronometers. This quickly became known as Railway Time. Improvements in worldwide communication further increased the need for interacting parties to communicate mutually comprehensible time references to one another. The problem of differing local times could be solved across larger areas by synchronizing clocks worldwide, but in many places that adopted time would then differ markedly from the solar time to which people were accustomed.

Timekeeping on the American railroads in the mid-19th century was somewhat confused. Each railroad used its own standard time, usually based on the local time of its headquarters or most important terminus, and the railroad’s train schedules were published using its own time. Some junctions served by several railroads had a clock for each railroad, each showing a different time.

The first known person to conceive of a worldwide system of time zones was the Italian mathematician Quirico Filopanti. He introduced the idea in his book Miranda! published in 1858. He proposed 24 hourly time zones, which he called „longitudinal days“, the first centred on the meridian of Rome. But his book attracted no attention until long after his death.

Scottish-born Canadian Sir Sandford Fleming proposed a worldwide system of time zones in 1879. He advocated his system at several international conferences. In 1879 he specified that his universal day would begin at the anti-meridian of Greenwich (180th meridian), while conceding that hourly time zones might have some limited local use. He also proposed his system at the International Meridian Conference in October 1884, but it did not adopt his time zones. The conference did adopt a universal day of 24 hours beginning at Greenwich midnight, but specified that it „shall not interfere with the use of local or standard time where desirable“.

By about 1900, almost all time on Earth was in the form of standard time zones, only some of which used an hourly offset from GMT. Many applied the time at a local astronomical observatory to an entire country, without any reference to GMT. It took many decades before all time on Earth was in the form of time zones referred to some „standard offset“ from GMT/UTC. By 1929, most major countries had adopted hourly time zones.

Zdroj