Newtonovy zákony

Zdroj

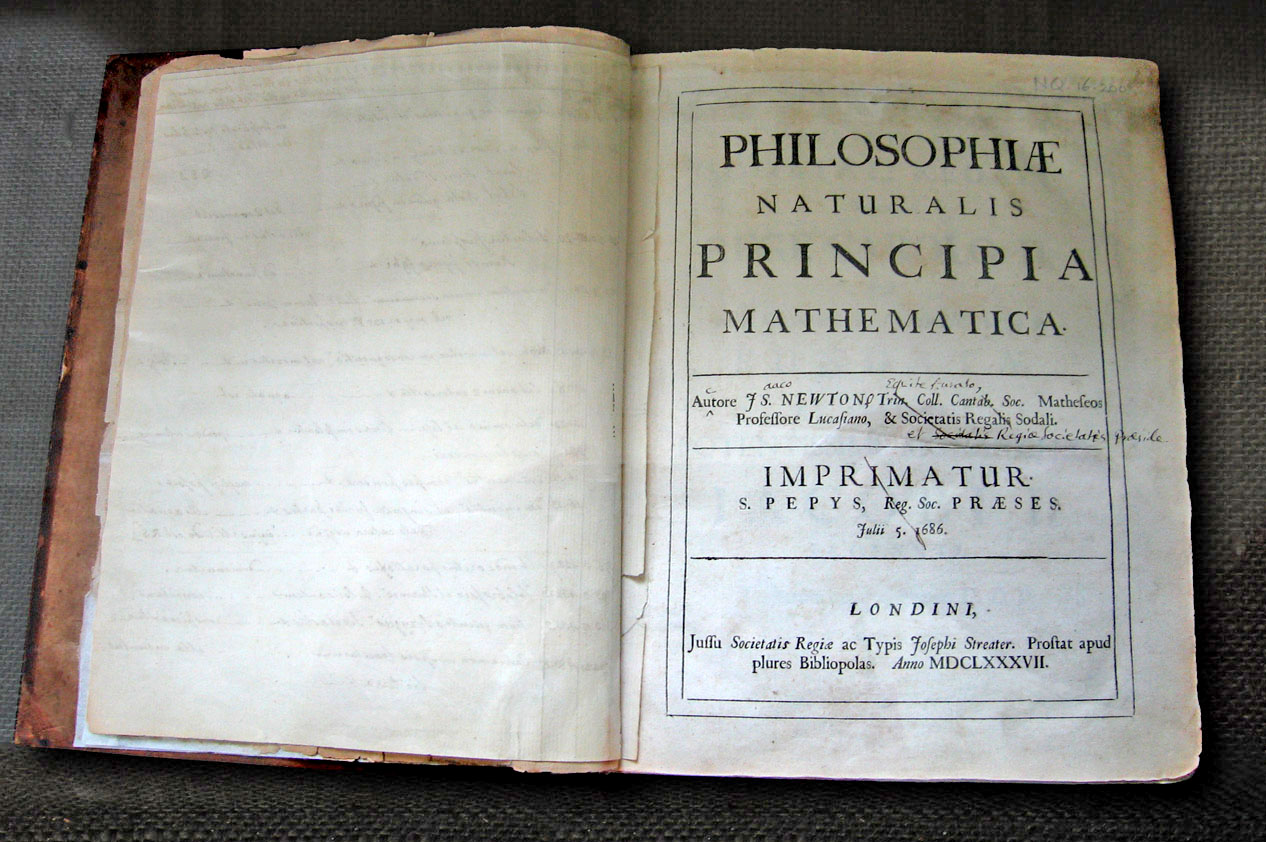

Matematické základy přírodních věd Isaaca Newtona se na více než dvě století staly základním kamenem fyziky a vědeckého myšlení vůbec. Jde o první systematickou fyzikální teorii.

Isaac Newton publikoval své zákony pohybu v roce 1687 v knize nazvané (v českém překladu) „Matematické základy přírodních věd“, která obsahuje i výsledky jeho studia konkrétních mechanických jevů, teorii gravitace, názory na světlo a mnohé další. Jeho dílo se stalo počátkem nové éry v přírodních vědách.

LAW I.

Every body perseveres in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed thereon.

PROJECTILES persevere in their motions, so far as they are not retarded by the resistance of the air, or impelled downwards by the force of gravity. A top, whose parts by their cohesion are perpetually drawn aside from rectilinear motions, does not cease its rotation, otherwise than as it is retarded by the air. The greater bodies of the planets and comets, meeting with less resistance in more free spaces, preserve their motions both progressive and circular for a much longer time.

LAW II.

The alteration of motion is ever proportional to the motive force impressed; and is made in the direction of the right line in which that force is impressed.

If any force generates a motion, a double force will generate double the motion, a triple force triple the motion, whether that force be impressed altogether and at once, or gradually and successively. And this motion (being always directed the same way with the generating force), if the body moved before, is added to or subtracted from the former motion, according as they directly conspire with or are directly contrary to each other; or obliquely joined, when they are oblique, so as to produce a new motion compounded from the determination of both.

LAW III.

To every action there is always opposed an equal reaction; or the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal, and directed to contrary parts.

Whatever draws or presses another is as much drawn or pressed by that other. If you press a stone with your finger, the finger is also pressed by the stone. If a horse draws a stone tied to a rope, the horse (if I may so say) will be equally drawn back towards the stone: for the distended rope, by the same endeavour to relax or unbend itself, will draw the horse as much towards the stone as it does the stone towards the horse, and will obstruct the progress of the one as much as it advances that of the other. […]

Úkoly:

- Přečtěte si formulace Newtonových zákonů a připojené komentáře. Pokuste se znění zákonů přeložit do češtiny.

- Najděte příklady ze života, které praktické použití jednotlivých zákonů ilustrují.